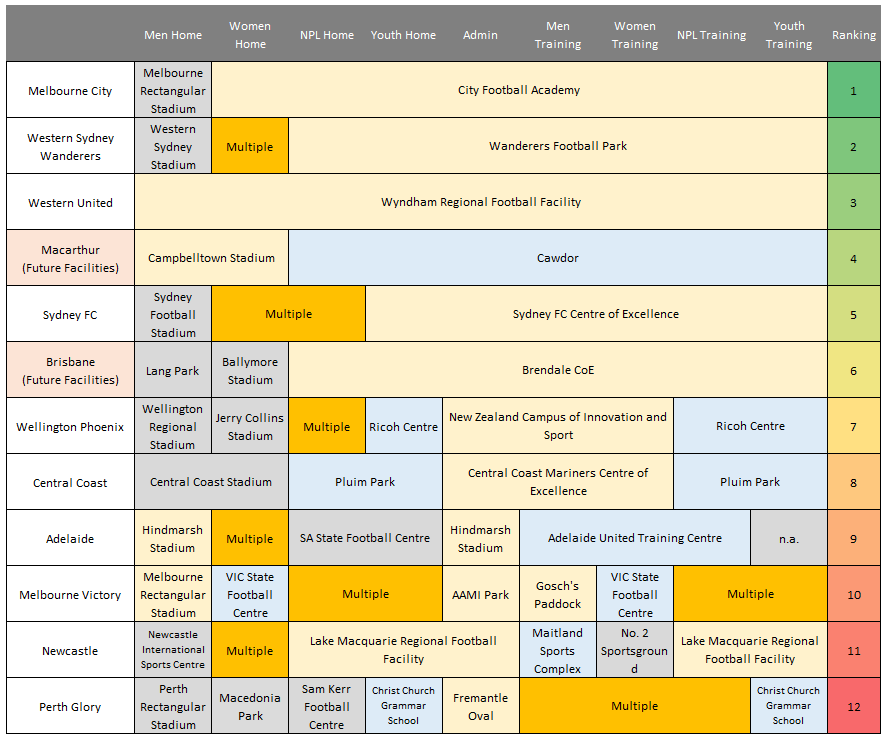

There are constantly conversation about A-League facility issues but these are often specific and viewed in isolation. We feel that there has been limited holistic analysis of A-League club facilities arrangements. As such, we have analysed the facility arrangements of every current A-League Men club. In doing so, we uncovered a number of lessons and insights which every football fans in Australia should know.

Lesson 1: Outer suburb councils are the A-League’s most important facilities stakeholders

The top four places in our club facility rankings went to clubs that has strong relationships to outer suburb councils. Councils control and fund the vast majority of sporting infrastructure in Australia. However, whereas inner city council facilities are often at capacity (or leased to existing long term tenants), outer suburb councils have a different set of characteristics. They have more land available for development, they are underserviced by community institutions, and they have a desire to deliver their growing regions with adequate community services. These factors make them perfect partners for A-League clubs and in recent years have helped deliver some of the league’s best facilities including:

- City of Moreton Bay delivering up to nine pitches for Brisbane Roar (the club will operate minimum two)

- City of Playford delivering two pitches for Adelaide United to operate

- City of Casey delivering five pitches for Melbourne City to operate

- City of Wyndham delivering a three pitch training facility for Western United to operate, as well gifting land to the West Melbourne Group to develop

- City of Campbelltown delivering economically viable facilities to Macarthur FC and assisting with planning approval and grant applications for its two potential training facilities

Attempts to work with inner city councils on the other hand have proven problematic. In most cases their facilities are already occupied, and in other cases the extreme land scarcity creates significant political pressure. In a deflating example, Melbourne Victory worked with the City of Maribyrnong for years on its Footscray Park project before encountering AFL aligned community lobbying efforts which saw the project collapse.

Outer suburb headquarters are common in football, with the strategy used by major European teams to deliver large training and administrative bases. Those teams however maintain match day facilities in centrally located areas. Examples include Tottenham FC and New York City FC who train far from their home grounds in London and New York respectively.

Lesson 2: There has been a recent boom in A-League facility investment

Assessment of A-League facilities surprised us with a recent trend – there has actually been a huge recent boom in facility development. Multiple venues have been constructed in recent years (Wanderers 2019, Melbourne City 2022, Sydney FC 2023, Western United 2024) and more are planned (Brisbane 2024 and potentially Perth and Macarthur).

Why has this been the case? The most important change in recent years has been the growth of A-League club operations. At the A-League’s inception, clubs only comprised of a single senior men’s team. Stakeholders weren’t prepared to provide low cost facility access to these entities as they are also set up as for-profit companies and delivered minimal community benefit. Today though, clubs comprise ALW teams, NPL programs and Youth programs. NPL and Youth program have the added advantage of often operating under a separate non-for-profit entity. These operations provide more need for facilities and more community benefit. As a result clubs have had to increase their search for long term facilities, and key stakeholders, such as local councils, have been more willing to work with clubs.

However these is a secondary push we have recently seen. Clubs themselves are used as pawns in a property development game. Western United and Macarthur were founded by Property Developers who Partnered with Local Councils. This is different to the past, when A-League clubs which were founded with different intentions in mind. Some clubs were established to service a football demand (like Melbourne Victory who rented facilities at inception), some clubs were founded by existing communities (like the Brisbane Roar which were formed by the Lions FC community who already owned facilities at inception). This new property development dynamic has seen councils and facilities play a bigger role in A-League expansion.

Lesson 3: Clubs that don’t operate their own facilities often lose out

The more facilities a club operates, the greater its growth opportunities and resilience. Long term operational deals with councils (or in Sydney FC’s case, a university) appear to be the best. Clubs can hold their own fan days (Melbourne City), ALW games (Wanderers), and even look to earn revenue from other clubs sub-leasing their grounds (potentially Western United with the Melbourne Rebels).

Short term arrangements can and do leave clubs homeless. This happened recently when Perth Glory were unable to renegotiate their tenancy with WA Rugby. Even long term arrangements can be problematic if clubs don’t operate the facilities themselves. An example of this is when Brisbane Roar were forced to leave their Ballymore training base due to poor pitch conditions caused by Rugby teams who had priority over the facility. Even football managed facilities can be problematic. For example, even though many State Football Centres have housed A-League teams as tenants, political pressure from other local clubs can force A-League clubs out, this is one of the reason Canberra United has lost support from Capital Football.

Interestingly though even though operational control of facilities is to be prioritised, ownership of facilities may not actually be the best option for every club. Property ownership is extremely valuable in Australia and as a result can be subject to business threats. For example, the Mariners Centre of Excellence was once held by the same entity which held the club, however when Michael Charlesworth sold the club, he held onto the property. This means that even though the Mariner’s name was used to secure Federal Government funding for the facility, the club now rents the very same venue from a private owner. This may be especially important for Macarthur FC, where its owners have purchased land for the club to train on. If there was ever a change in the ownership or the land became more valuable as a different development, Macarthur may lose their training ground.

The advantage of an operating lease over ownership also includes optionality. Melbourne City were able to relocate the club quite quickly from Bundoora to Casey as they could leave their lease. They now enjoy better facilities.

There is a final critical important advantage of operating leases over ownership and that is costs. Sport facilities don’t make money, their government business cases are often inclusive of broader economic impacts (including hotel occupancy, and increases in local economy consumption). This is important for Western United (or more accurately the West Melbourne Group) who intend to own their stadium. If the stadium costs go beyond current forecasts WMG may find they don’t own an asset, but rather a massive cash black hole. A long term operating lease on the other hand can more effectively cap a club’s expenses. Councils manage the facility maintenance and club worry about the football.

Lesson 4: Elite Facilities serve an important purpose but come at a cost

Believe it or not, there are many opportunities to access to world class facilities. Clubs can do this by renting stadium administration facilities (Melbourne Victory at AAMI Park), university facilities (Sydney FC at Macquarie University) or even a sports science hub (Wellington at the New Zealand Campus of Innovation and Sport). These arrangements deliver world class facilities however often involve high rental fees. These facilities also often have an inability to host all club youth and community programs and can also involve sharing arrangements with other sports. Each situation is unique, but ultimately clubs typically don’t have the strong rights in these agreements as they would for more basic council facilities.

A more talked about example of this dynamic is in relation to major match day venues. Venues like the Sydney Football Stadium, Melbourne Rectangular Stadium, Perth Oval etc. tick all the boxes for a world class facility and provide superior spectator and broadcast experiences. However they also come with operational challenges. These stadiums are incredibly expensive to build and rent which often contributes to the financial instability of clubs and potentially even ownership instability. This was one of the contributing factors to the recent Perth Glory ownership collapse. These stadium are also often rented by other stakeholder which causes scheduling issues and pitch quality challenges.

To avoid these challenges, some recent A-League matches have been played at smaller stadiums including Dolphin Stadium, Macedonia Park and the Wyndham Regional Football Facility. This has shown there may be a changing appetite from the A-League regarding these big stadiums, however for many A-League clubs these stadiums are their only real playing options. Club viability is therefore contingent on signing financially sound stadium deals. These greatly impact many aspects of a club’s business plan including general admission pricing and season ticket marketing.

It must be said though that A-League clubs have enjoyed greatly improved major match day facilities in their time, with multiple redevelopment with A-League use in mind. Upgraded stadiums include Perth Oval and Hindmarsh Stadium whilst new stadiums have been built including Western Sydney Stadium, Sydney Football Stadium and Melbourne Rectangular Stadium. These projects total billions of dollars in value, but continue to require high rental fees.

These stadium rental negotiations are key but many A-League are unusually vulnerable in this regard especially compared to NRL and AFL counterparts. AFL and NRL clubs tend to have larger crowds which are more suited to these facilities and make stadium deals more sustainable. AFL and NRL clubs also tend to enjoy the status of being a facilities major tenants, which means they have greater negotiating power and future developments are done with them front of mind. The few A-League clubs that have more negotiating power are either primary tenants (Adelaide, Central Coast) or have strong relationships with facility owners (Western United, Macarthur).

I think clubs need to think more creatively with these facilities to make deals more impactful, especially when they only have one stadium option. They should consider:

- Only opening smaller parts of stadiums in line with their expected attendance to save money and improve atmosphere.

- Allowing more general admission tickets and general admission memberships to improve efficiency of seating usage.

- Programming double headers when these can result in cost saving.

The key lesson of all of this? A-League clubs need to get these stadium contracts right, but realistically they have less negotiating power to do so.

Lesson 5: Every club has specific circumstances

There is no one size fits all approach. Some University relationships work (Sydney) and some don’t (Newcastle). Some council relationships work (Adelaide) and some don’t (Brisbane and City of Logan). A few characteristics to consider for your club though include:

- The quality of club management: This has a big impact on facility relationships. Brisbane and Perth have demonstrated historically poor stakeholder management and as a result have a volatile facilities history.

- Ownership Stability: Even the best run club can’t enter into long term facility contracts if stakeholders are unsure whether the club will exist in the future. This is one of the reasons Newcastle and Perth don’t have long term facility arrangements.

- Local club ecosystem: Where an A-League club is seen as a competitor to other local clubs it can face opposition to facility usage such as when Western United were rejected from playing out of Lakeside Stadium. Where A-League clubs are seen differently in their communities (a collaborator rather than competitor) they enjoy better access to facilities, such as Central Coast at Pluim Park.

- Money: Wealthy clubs like Melbourne City can fund their own facilities (including the abandoned Bundoora Facility). Poorer clubs though are more reliant on grants and subject to suboptimal outcomes, just as Perth was when it required temporary upgrades to Macedonia Park.

In conclusion

There are many lessons to be learnt in the A-League’s facility story, but recent trends actually paint a bright future. Contrary to common belief A-League clubs and enjoyed significant facility funding and have a pipeline of facility projects that will put the league on a good footing in years to come.

Many people view the match day venue problems as be all and end all, and there is truth to this, but the rental arrangements here are transient and as we have seen, the league is more open to smaller match day venues now than ever before. Creative clubs can find a way to make match days work.

It is actually club operated facilities which should be the focus of conversation, as they are more critical to club resilience, and once established actually provide clubs with long term foundations. We saw the importance of this post the NSL. Clubs with long term facility arrangements (South Melbourne, Melbourne Knights) are still around today but those without (Northern Spirit, Parramatta Power) are not.

A-League clubs are not assured a future. Financial Sustainability and marketing based relocation have threatened – and ended – clubs before. In the future, promotion-relegation may also threaten club status. Club operated facilities though can offer a life line and resilience to clubs, ensuring they remain a long term feature of the community and don’t go the way of North Queensland Fury or the New Zealand Knights.

Financial sustainability and resilience. This is the basis we have used to rate and judge A-League club facilities in our analytical series. Overall though we are very optimistic about the future of the A-League Facilities, and more generally Australian Football Facilities. Alongside increased A-League investment we have seen improved investment in State Football Centres and we also believe the NSD will further assist facility development, noting it has already helped Avondale secure a facility that would make Melbourne Victory blush!

We hope you enjoyed this series and learnt a little about facilities in the A-League.

One final note

Finally, just to shatter the funding fallacy, A-League have received at least $120m in funding commitments for facilities. This is excluding major home stadium redevelopments and rebuilds. It may not be as much as some AFL clubs but it is still significant.

- Adelaide United: $700,000 Playford Training Base

- Brisbane Roar: $9m Logan Training Base

- Brisbane Roar: $22m Brendale Training Base

- Central Coast Mariners: $10m Centre of Excellence

- Macarthur FC: $16m Centre of Excellence

- Melbourne City: $23m Centre of Execellence

- Melbourne Victory: $10m for future Training Base

- Sydney FC: $20m Centre of Excellence

- Western Sydney Wanderers FC: $10m Wanderers Football Park

- Western United: Council Funding of WRFF